Today we’re covering the final case from our namesake, the the murder of Marion Gilchrist and the trial of Oscar Slater.

THE MURDER

It was the 21st of December 1908 in Glasgow’s Square Mile of Murder. At 7pm young maid Helen “Nellie” Lambie left the flat where she worked for Marion Gilchrist, leaving her 83-year-old mistress in the flat at 15 Queens Terrace, West Princes Street. Nellie left every day at 7 to fetch the newspapers for Miss Gilchrist, a task that usually took her 10 minutes. It was during this short period of time that Nellie Lambie was running errands that her wealthy employer was murdered, and an injustice of historic proportions was set into motion. But we’ll get to all that.

Before we get to Oscar Slater, let’s rewind a bit to when Nellie Lambie leaves the flat. Miss Marion Gilchrist was a wealthy, unmarried woman, living in a well appointed first floor flat at 49 West Princes Street, which is now in an area of Glasgow called Woodlands. This is the furthest west location that we’ve seen in the Square Mile of Murder and now falls on the opposite side of the motorway that was built through the centre of the area. Living below Miss Gilchrist in the main door flat on the ground floor was Mr. Arthur Adams and his two sisters. Adams heard a thud on the ceiling of his dining room followed by three taps, which was a prearranged signal between him and Miss Gilchrist. If ever she was in trouble, they agreed, she should tap on the floor and Adams would come up to help at once.

He and his sisters were pretty sure that those three taps were the signal and so Adams went out his front door and went through the close door that led to the stairs up to Miss Gilchrist’s flat and one unoccupied flat on the second floor. He was surprised to find the close door unlocked, it was usually locked. He continued on and reached Miss Gilchrist’s door and rang the bell. He got no response and couldn’t hear anything inside so he rang again. He looked through the glass panels on either side of the door and saw that the gas lights were lit in the entryway. He rang one more time. Then he heard what he thought sounded like someone chopping sticks. He assumed this was Nellie in the kitchen, so he went back downstairs.

But his sister, Laura Adams, was not satisfied with her brother’s investigations and was convinced something was wrong upstairs. She sent him back upstairs where he rang again. This time it was completely silent. He heard someone coming upstairs behind him and saw Nellie Lambie returning from her errands. He told her what he had heard and she said the noises were probably some pulleys in the kitchen that needed oiling. Nonetheless he said he’d stay put until he was sure everything was all right. Nellie unlocked two of the three locks on the door (the third was only locked overnight) and headed towards the kitchen to check the pulleys. Arthur Adams could see into the entryway which had two doors on the right and two doors on the left. As Nellie headed left to the kitchen, a man appeared from one of the bedroom doors on the right. The man wore a light overcoat and Adams later said the man looked to be a “gentleman”. This mysterious man stepped up to Adams almost as if to speak to him, but instead stepped past Adams, over the threshold, and disappeared quickly down the stairs. Adams noted that Nellie Lambie didn’t seem surprised to see this man, and assumed she must have known him.

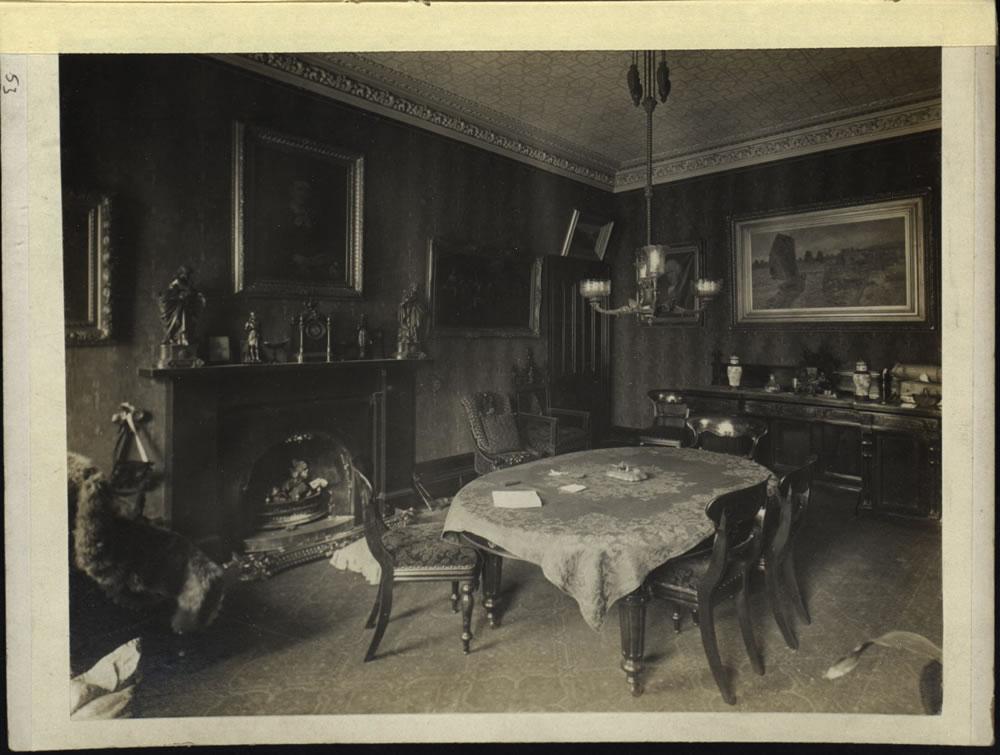

Nellie continued on to the kitchen where she reported that nothing was wrong with the pulleys, but Adams was more concerned that Miss Gilchrist was nowhere to be seen. Nellie went into the dining room and let out an awful scream. She called out: “Oh, come here!” Adams followed her and saw Miss Marion Gilchrist lying on the floor in front of the fireplace. She had a rug thrown over her head and was surrounded by blood. Upon seeing this gruesome sight he decided to go after the mystery man, he told Nellie to go to the close door and stay there until he got back. He sprinted down the stairs and into the street. He ran in both directions, but couldn’t find the man from the close. When he returned Nellie Lambie had found a policeman. They all went back into the dining room and removed the rug from Miss Gilchrist. They saw that she had been beaten savagely around her head. But she was still breathing. Arthur Adams ran out to fetch a doctor from across the street. When the doctor arrived Miss Gilchrist had died. The doctor pointed out that a bloodstained chair next to the body looked to be the murder weapon. This is the last we’ll hear from the doctor in this case. He was never questioned nor did he appear at the trial.

THE INVESTIGATION

As the police started to look around the flat they found a lit gas lamp in the spare bedroom that Nellie swore hadn’t been lit when she left. Below the lamp was a used match and a box of Runaway brand matches, a brand that Lambie said they did not use in the house. She had never seen them before. And on the table beside the matches was a gold watch and chain, a tray with some jewellery, and a wooden box holding documents that had been broken open and clearly rifled through. Papers were strewn all over the floor. When asked if anything was missing from the room, Nellie could only come up with one thing: a crescent shaped, diamond brooch.

When police asked Nellie and Adams to describe the man who had exited the flat, they found their witnesses to be less than helpful. Nellie said she had barely seen the man, and Arthur Adams had left his glasses downstairs, and hadn’t gotten a good look at the man.

The description the police cobbled together was: “A man between twenty-five and thirty years of age, 5 feet 8 or 9 inches in height, slim build, dark hair, clean shaven; dressed in light grey overcoat and dark cloth cap. Cannot be further described.” They sent the description to pawn shops around the city along with information about the stolen crescent brooch. Nellie for her part left the flat that night to tell Miss Gilchrist’s niece, Miss Margaret Birrell, know about the murder.

Police believed that the murderer was someone whom Miss Gilchrist knew, or was at least familiar enough with to let him into her house. They were immediately suspicious of Nellie Lambie and looked into her boyfriends and if she had told anyone about the jewellery in the flat. Miss Gilchrist was laden with jewels and rumour had it she secreted expensive pieces of jewellery all over the flat and may have even sewed some into the curtains. She had over £3,000 worth of jewellery hidden around the flat. But only the brooch had been taken. She was also terrified of burglars and intruders which was why she had set up a signal with the Adams family downstairs. All of this points to the idea that she wouldn’t let just anyone into her home.

By Christmas Eve the police still didn’t have any leads, but they lucked into some information in the form of an eyewitness. 14-year-old Mary Barrowman told police, after some convincing by her mother, that she had been walking along West Princes Street at 10 past 7 on December 21st and had seen a man rush from Miss Gilchrist’s close and then dash down the street. She said that the man bumped into her and then turned down West Cumberland Street and disappeared. Her description of this man was more detailed, but it also differed wildly from the one given by Nellie Lambie and Arthur Adams. So much so that police decided they were probably looking for two different men. They issued a statement saying that they were looking for the first man who matched the first description and a second man: “Aged twenty-eight to thirty years of age, tall and thin, clean shaven, nose slightly turned to one side (thought to be the right side); wore a fawn-coloured overcoat (believed to be a waterproof), dark trousers, tweed cloth cap of the latest make, and believed to be dark in colour, and brown boots.” These descriptions were published in the Glasgow newspapers on Christmas Day.

On Christmas Day, the police also got a tip from a bicycle dealer named Allan McLean. McLean had read about the stolen brooch and told police that another member of a gambling club he belonged to had been trying to sell a pawn ticket for a diamond crescent brooch. He told police he could show them the house that this man lived in. He only knew the man’s first name: Oscar.

THE SUSPECT

At 69 St George’s Road police found a plate on the door that read “A. Anderson, Dentist.” But the place wasn’t a dentist office, but instead the residence of one Oscar Slater. Born Oskar Josef Leschziner in Oppeln, Upper Silesia, Germany to a Jewish family in 1872. He had left Germany in 1893 and moved to London where he had worked as a bookmaker using various Anglicised names including Anderson before settling on Slater as his surname. He moved to Edinburgh in 1899 and Glasgow in 1901 where he lived with his mistress, Madame Andrée Junia Antoine. Oscar Slater billed himself as a dealer of precious stones, but more likely made his living through gambling. And Madaame Junia entertained men for money in the couple’s flat while Oscar was out “working”.

So police were quite pleased to come upon this veritable den of ill-repute. But they had a problem, nobody was home. Earlier that day, Oscar Slater and Madame Junia had left Glasgow for Liverpool and had plans to sail to New York on the Lusitania. Police believed that this sudden departure must have been a flight from justice. The descriptions had been published in the newspaper that day, surely Slater had seen this and realised he had to get out of town.

But they had a problem, that brooch that Slater had pawned? It wasn’t the same brooch that had gone missing from Marion Gilchrist’s flat. And the brooch pawned by slater had been pawned way back on November 18th. They didn’t let the fact that they had no evidence deter them though, quite the contrary. They became convinced that Oscar Slater was their man.

Police found out that Slater and Madame Junia were travelling on the Lusitania under the names Mr. and Mrs. Otto Sando and they alerted the New York Police. When the ship docked on January 2nd, 1909, Slater was arrested and taken to the Tombs prison. Newspapers back in Glasgow printed Slater’s name and photograph and announced he had been arrested for the gruesome murder. The police now had to extradite Slater back to Scotland, but first they sent their three main witnesses to New York to identify him. Even though Nellie Lambie and Arthur Adams said they wouldn’t be able to identify the man they saw and the man that Mary Barrowman had seen was very different from the man the other two had encountered, they still sent three people all the way across the Atlantic! And they had a plan to solve their differing descriptions. They coached Nellie and Mary until their descriptions lined up and just for good measure they put the two girls in a cabin together for the 12 day voyage across the ocean.

The three did identify Slater in a New York courtroom (after seeing him led down the hallway in handcuffs), but this was also far from perfect. Nellie and Mary reportedly recognised Slater in the hallway, but Arthur Adams had to ask the two girls if the man in handcuffs was the right man.

Slater had an American lawyer who advised him to resist extradition. But Slater insisted he was innocent and volunteered to return to Scotland to clear the whole thing up.

While waiting in the Tombs Slater wrote a letter to a friend where he discussed the crime he was accused of. He knew so little about the murder of Marion Gilchrist he thought the crime had taken place on December 22nd, not the 21st. He had already told police he had never met Miss Marion Gilchrist and had never been to her house. He also explained the discrepancy between the name on his front door, A. Anderson, and his own name. After moving to Glasgow Slater had met a Scottish woman and the two were married. Which turned out to be not so good for Slater because this woman was an alcoholic who spent money wildly. He left her but they weren’t divorced, and he often used different names to keep off her radar when she would come looking for money. Soon after he met Madame Junia in London and the two lived together in New York for a few years before returning to Glasgow in 1908.

Now might be a good time to describe Oscar Slater. He was known to be a well-dressed man who had his shirts custom made. He was broad-shouldered, had a prominent nose, and wore a small mustache. He is often described as being “distinctly foreign looking at a time when Glasgow didn’t have many “foreign-looking” residents. All of this is to say that Slater “looked” Jewish at a time when many people in Glasgow, especially the people in Glasgow’s upper echelons of society, held fairly anti semitic views. Starting in the 1880s Scotland had seen an increase of Jewish immigrants fleeing from persecution and pogroms in the Russian Empire. Many settled in poorer areas of Glasgow like the Gorbals which was already home to many Irish and Italian immigrants. By 1897, Glasgow had a Jewish population of about 4,000. History is fuzzy on just how much anti semitism contributed to Slater’s identification as the murderer but it’s safe to say that Mary Barrowman’s description of a man with a large, bent nose (or hooked nose as some sources describe it) certainly fits with common anti semitic stereotypes. Scholar Ben Braber has written about Slater’s case and came to the conclusion that police and court officials were influenced by xenophobia and anti-Jewish sentiment. Add that to Slater’s chosen profession as a gambler and his chances of getting a fair trial were not looking good.

So Slater returned to Scotland where he told police that his trip to New York had been planned at the beginning of December. He had written to friends in America as early as December 7th about his plans to head out to San Francisco to start a gambling club there. He also had an alibi for the night of the murder. Slater spent the afternoon at a billiards club on Renfield Street with two buddies. He left there at around 6:30pm and returned home to have dinner with Madame Junio and her maid Catherine Schmalz. He stayed in his house until a little after 8 when he went down to the close door to smoke. A grocer saw Slater smoking and recognised him as a customer. But this grocer was never called at trial. He was also seen gambling at the Sloper Club later that night.

Despite this, Slater was picked out of an identity parade by more witnesses who came forward saying they had seen him around West Princes Street the night of the murder. And it’s important to note they came forward after Slater’s picture had been printed in the newspapers. To make matters worse, the other men in the line-up were nine policemen and two railway officials, all of whom were native Scots. Slater was the obvious odd-man out. And so his trial was set for Monday May 3rd in Edinburgh.

THE TRIAL

His trial was presided over by Lord Charles John Guthrie, who from the start of the trial made it very clear that he thought Slater was guilty. The prosecution’s whole case hinged on eyewitness testimony. On the stand Arthur Adams was still hesitant about whether Slater was the man he had seen in the flat. But Nellie Lambie and Mary Barrowman both testified that they were absolutely sure. The prosecution also hammered what he described as Slater’s “flight from justice” to New York. But the defense put up witnesses that gave Slater an alibi for the night of the murder as well as witnesses that confirmed that Slater’s trip to America was planned well in advance.

When the Judge addressed the jury, he made sure to emphasise Slater’s “poor character”. He said: “He has maintained himself by the ruin of men and on the ruin of women, living for years past in a way that many blackguards would scorn to live…The many’s life has been not only a lie for years, but is so today. We do not know whether he ever did an honest day’s work in his life.”

The jury took an hour and ten minutes to deliberate and came back with a verdict of guilty. The jury voted 9 guilty, 5 not proven, 1 not guilty. Lord Guthrie sentenced Slater to death on Thursday May 27th, 1909.

When the verdict was announced, Slater shot up in his seat and cried out: “My lord, my father and mother are poor old people. I came on my own account to this country. I came over to defend my right. I know nothing about the affair. You are convicting an innocent man…I came over from America, knowing nothing of the affair, to Scotland to get a fair judgement. I know nothing about the affair, absolutely nothing. I never heard the name… I don’t know how I could be connected with the affair.”

His statement in court got the city’s attention, and soon enough many Glaswegians were lining up on the street corners to sign a petition that said the prisoner had not been adequately identified as the murderer and that alleged immoral character shouldn’t have been brought before the jury. The petition pushed for Slater’s sentence to be commuted. More than 20,000 people signed the petition. Slater’s lawyer sent the petition to the Secretary for Scotland, who commuted Slater’s sentence to penal servitude for life, two days before he was set to hang.

THE AFTERMATH

Slater was sent to Peterhead Prison. While there he wrote bewildered letters to his lawyers full of theories about what had actually happened to Miss Gilchrist. Meanwhile William Roughead, a well-known Scottish lawyer and amateur criminologist was busy writing up the facts of the crime and the case in an early example of true crime writing called, Trial of Oscar Slater which was published in 1910. After the book’s release, public opinion again swayed and many believed that Slater had been the victim of a grave injustice.

Roughead’s book convinced many influential people of Slater’s innocence, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. And in 1912, Doyle published his own work on the case, The Case of Oscar Slater, which was a thin volume based on Roughead’s account pleading for a full pardon for the prisoner. Doyle’s version of the crime also presented a theory not favoured by many at the time: that the murder hadn’t been looking for jewels or valuables in the flat, but rather some document, perhaps a will. All these very public pleas for Slater’s case to be reconsidered also reached someone very close to the case in the Glasgow police.

Detective John Thomson Trench had begun working to reexamine Slater’s case. Trench had joined the Glasgow Police Force as a constable in 1893 and by 1912 he was a Detective-Lieutenant. He had been involved with the Gilchrist case from the moment it was reported to the police. In fact, he said that Nellie Lambie had actually named the man she had seen in the flat the very night of the murder. And wouldn’t you know it, that name was not Oscar Slater. But once police found out about the missing brooch they pursued that lead above all else and became obsessed with Slater. Trench had to follow orders and put aside his own theories and feelings that Slater had been wrongly accused and convicted.

But as time passed, his concern that the true killer had never been caught and that the wrong man was sitting in prison weighed on Trench’s conscience. In 1914, He approached a well-known Glasgow lawyer, Mr. Cook, told him what he knew about the case, and asked for advice. The lawyer then approached ond of HM Prison Commissioners for Scotland who then wrote to the Scottish Secretary, Mr. McKinnon Wood. Wood wrote back on February 13th, saying that if Trench wrote up what he knew of the case the secretary would consider the matter.

So Trench sent over all the information and evidence he had, which set into motion the destruction of his career in the Police Force. Mr. Cook asked Mr. McKinnon Wood to hold an enquiry into Slater’s case and raised five questions:

- Did anyone on the night of the murder identify the man in the flat as anyone other than Oscar Slater?

- If they did, were the police aware of this and if they were why wasn’t this presented a trial?

- Did Slater flee from justice?

- Did the police know that Slater had given his name in Liverpool and had disclosed prior plans to travel on the Lusitania?

- Did one of the witnesses make a mistake about the date she said she was in West Princes Street?

Mr. McKinnon Wood appointed the Sheriff of Lanarkshire to conduct an enquiry into the case, but like everything else in this case so far, it was hardly fair or balanced. The enquiry was private, neither Slater or his lawyer were allowed to attend, the witnesses were not under oath and were simply asked to appear but could decline if they wanted. The enquiry was supposed to “in no way relate to the conduct of the trial” and The only people present were the Sheriff, his clerk, and the witnesses. Oh and the actual words of the witnesses weren’t transcribed. Instead the Sheriff dictated a summary of each witness’s testimony and when he didn’t like what they had said, he just left out that part of their evidence and put in asterisks instead.

Most of these asterisks related to the mystery man in the flat who is known in the report as “A.B”. According to the records, Detective-Lieutenant Trench testified that a Superintendent and two detectives went to A.B.’s house the day after the murder based on information give by Nellie Lambie. He didn’t know what had happened there, even though he had tried many times to find out. He was then instructed on December 23rd to take a statement from Miss Birrell about A.B.

Miss Birrell, who was Miss Gilchrist’s niece, had made a very interesting statement indeed. She noted that Miss Gilchrist wasn’t on good terms with any of her relatives and never had any family visitors. She said Nellie Lambie came to her house the night of the murder and told her she had seen and recognised the murderer. Miss Birrell said that Nellie had identified the murder as this man, A.B., she was sure of it.

Trench then recalled bringing up the matter of this A.B. to his superiors but being met with resistance, being told by the Chief Superintendent that another officer had decided that A.B. had nothing to do with the matter and that there was nothing else they could do. Trench was also convinced that Mary Barrowman was nowhere near Miss Gilchrist’s flat the night of the murder, and that he had taken statements from her employer and her sister that Mary had not been out on an errand the night of the 21st.

Both Nellie Lambie and Miss Birrell denied this recounting of events at the inquiry, the other members of the Glasgow police closed ranks and denied Trench’s version of the story. The secret inquiry concluded on April 25th and on June 17th, Mr. McKinnon Wood made a statement in the House of Commons saying that no case had been established which would justify any interference with Oscar Slater’s sentence. And on June 27th, the Government issued a White Paper on the matter, which was looked upon kindly by pretty much only the Glasgow Police and nobody else. Trench, for his bravery and attempt to see justice done, was suspended for consulting with a civilian about the case (the lawyer, Mr. Cook). He appealed his suspension to the magistrates who decided to dismiss him from the police altogether. When Trench wrote to Mr. McKinnon Wood (who had promised to protect Trench if he blew the whistle) asking for help, McKinnon Wood didn’t even bother to respond to his letter.

Trench had been in the military prior to joining the police, so when World War I broke out in August 1914, he joined the Army. He was well respected in the Army and was appointed Provost Sergeant of Stirling. But even though he had left the police behind, the police were still thinking about him. In May of 1915, Trench and Mr. David Cook were arrested on the charge of reselling stolen jewellery. It all related to a jewellery store burglary Trench had investigated in January 1914 and the whole accusation was very confusing. If you’re interested, you can read more about it in Jack House’s book Square Mile of Murder, which we’ll link below. Basically the Glasgow police were trying to frame Trench for making them look bad, but they didn’t succeed. The judge addressed the jury in their trial and made it clear that the evidence against the two men was flimsy at best and said that the two men should be found not guilty. And the jury did just that. Trench and Cook were released and Trench rejoined his Army unit. He died at age 50 in 1918.

Trench’s quest to bring justice to Slater wasn’t forgotten after his death. Eight years after his death, Trench’s journalist friend William Park published yet another book about the case this one called: The Truth about Oscar Slater. Park dedicated the book to Trench.

Slater meanwhile was still serving hard labour in Peterhead Prison. By this point it was 1927 and Slater had been there since 1909. It was customary in Scotland for life-sentence prisoners to be released after 15 years, but Slater was already up to 18 and had no release date in sight. But William Park’s book changed all that. Park’s book laid out Trench’s theory of the case which was this: A man whom Miss Gilchrist knew very well had gone to visit her that night. He hadn’t intended to killer her, he simply wanted a document from her. They argued and he struck her which caused her to fall and hit her head on the coal box. When he looked at Miss Gilchrist and saw she was still alive he realised that she would tell Nellie Lambie who had attacked her. So he decided he had to kill her. He used the chair in the dining room to beat her. The bell rang but he ignored it. Then he went into the second bedroom to find the document he was looking for. When he heard the door open he simply walked out. He knew that Nellie knew him and wouldn’t be suspicious of him being in the flat.

A copy of Park’s book was sent to the Secretary of State for Scotland, Sir John Gilmour, and newspapers took up a renewed interest in the case. On October 23rd, 1927, Empire News ran a statement supposedly from Nellie Lambie where she admitted she had known the man she saw leaving the flat but the police had convinced her she had made a mistake and pushed her to say she had seen Slater instead. Gilmour was convinced and on November 10th, 1927 he told the House of Commons: “Oscar Slater has now completed more than eighteen and a half years of his life sentence, and I have felt justified in deciding to authorise his release on license as soon as suitable arrangements can be made.”

The press wasn’t exactly thrilled with his decision because they saw releasing Slater as a way to avoid looking into the whole case. Slater was released from Peterhead on November 14th. After his release, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle took up Slater’s cause once again and sent a letter to all M.P.s stating that an enquiry into the trial should be made. This time the Secretary of State agreed and arranged an enquiry to be conducted by the Scottish Court of Criminal Appeal.

Slater’s appeal was held in the summer of 1928 and when all the evidence was presented the court found that Lord Guthrie’s instructions to the jury had been prejudicial and that Slater’s conviction should be vacated. The Secretary of State made an address in the House of Commons saying that Slater should put forward a request for any amount of money he desired and it would be considered by the government. Slater responded saying he wouldn’t make any claim for compensation. Despite this, Sir John Gilmour sent Slater a letter saying the government would send him a payment of £6000 (which would be worth about £379,767 today) if he agreed to those terms. Slater agreed, even though he probably should have consulted his lawyers. Slater had to pay the costs of his appeal himself which cost about £1500. Following his release he lived a quiet life in the seaside town of Ayr on the west coast of Scotland. Oscar Slater died on February 3rd, 1948. He was 75.

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED

So what did happen on the night of December 21st, 1908? Who killed Miss Marion Gilchrist? Well we should tell you that eventually Mary Barrowman came clean and admitted she had never been in West Princes Street. She hadn’t bumped into the killer, hadn’t seen anything at all. Her alcoholic mother had forced her to tell the story to claim some of the reward money. Nellie Lambie was said to have prepared a statement to be released upon her death, but no statement was ever released.

So the question becomes, who was A.B.? The man Trench so strongly believed was the killer? Over the years A.B. has been identified as Dr. Charteris, one of Miss Gilchrist’s nephews. When asked years after the murder if he was A.B. Dr. Charteris denied it, but who wouldn’t?

In Square Mile of Murder, Jack House puts forth that it wasn’t just Dr. Charteris who had a hand in Marion Gilchrist’s death, but that two men were involved. If we look at Miss Margaret Birrell’s statement that said Miss Gilchrist wasn’t on good terms with her family, we start to see the whole picture come together. Marion Gilchrist had inherited a massive amount of money from her father when he died which was a source of constant strife between Mis Gilchrist and her sisters. And there’s another little wrinkle here: Marion Gilchrist gave birth to an illegitimate daughter when she was young, and she had planned to leave all of her money to that daughter and her grand-daughter. This angered the rest of her family who all wanted in on her Will.

So Jack House proposes that Dr. Chateris had help from one Austin Birrell, name sound familiar? He even had conversations with one of Austin Birrell’s nephews who told him the whole family knew that “Uncle Austin had done the murder.” So how did Birrell and Charteris do it?

Nellie Lambie easily could have let them in, she knew them after all, or they arrived right after she left. They knew Miss Gilchrist kept her documents in the spare bedroom, so once they were in the flat they split up. Birrell took Miss Gilchrist into the dining-room and Charteris went to the bedroom to search for the document. House believed that Miss Gilchrist knew what they were up to and started giving Birrell Hell. And BIrrell was apparently known to have epileptic fits that would send him into a blind rage, which House believes is what happened next. He struck Miss Gilchrist and she fell and hit her head on the coal box. The sound of her falling was the thud the Adams family heard downstairs. Realising that he was in trouble, Birrell decided to double down and started attacking Miss Gilchrist with the chair. Which sent blood everywhere.

But because Birrell was holding the chair he would have kept some blood off of his body and clothes. But he wouldn’t have been able to keep it off his hands. And indeed, William Roughead had a photograph of the chair in question with a very distinct handprint in blood. But the Glasgow police, though they had used fingerprinting in previous cases, didn’t use it in this one. House wrote that this bloody handprint is why we know two men were involved. If only one man had killed MIss Gilchrist, there would be evidence of blood in the bedroom and on the documents, but there was none. House surmised that Birrell ignored the bell when Arthur Adams first checked. He threw the rug over Miss Gilchrist’s head and left the flat. Instead of leaving the building, he went upstairs to the landing of the unoccupied flat and waited until Charteris was done and the hallway was clear. Charteris found what he was looking for, and simply strolled out of the bedroom, past Nellie Lambie and Arthur Adams. With Adams and Lambie inside the flat, Birrell could run down the stairs and the two men booked it to Charteris’s house with plenty of time to compose themselves and change before the police arrived to question them that evening.

And that is the story of the murder of Miss Marion Gilchrist, the unfair trial and imprisonment of Oscar Slater, and the last of Glasgow’s Square Mile Murders.

RELATED EPISODES:

10: The Square Mile of Murder Poisoner

20: Square Mile Murder at Sandyford Place

FURTHER READING:

Square Mile of Murder by Jack House

The Trial of Oscar Slater by William Roughead

The Case of Oscar Slater by Arthur Conan Doyle

The Case of Oscar Slater – National Records Scotland

The trial of Oscar Slater: Scotland’s worst ever miscarriage of justice at Peterhead Prison

The Oscar Slater Murder Story by Richard Whittington-Egan

Voices from our Archives: Oscar Slater (1872-1948) – Open Book

New novel sheds further doubt on key murder witness

BBC Radio Scotland – Denise Mina’s Case Histories – Clips

Understanding the Antisemitic History of the “Hooked Nose” Stereotype

The Gorbals and the Jews of Glasgow , by Kurt Fleischmann

History of the Jews in Scotland

The implications of historical and contemporary anti-Semitism in Gl…

How Sherlock Holmes’ creator saved the ‘Scottish Dreyfus’

The Trial of Oscar Slater (1909) and Anti‐Jewish Prejudices in Edwardian Glasgow